In 1912, a German concertmaster named Siegmund Hess passed away, leaving behind a school and a list of belongings including two violins seemingly lost to time.

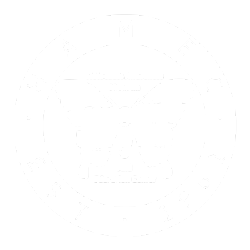

It wasn’t until more than 100 years later that Hess’s great-granddaughter, Eva Neubeck, would bring those violins back into the light. Neubeck, a retired social worker for Minneapolis public schools, said she was never much of a researcher.

But when her mother passed away in 2018, it sparked something within her.

“I don’t know whether it was grief or just new curiosity as one loses a parent,” Neubeck said.

Great-grandfather’s dossier

That curiosity kept going throughout the COVID lockdown. In 2020, Neubeck went through her mother’s belongings. She recalled an old bench her mother had shown her a few years before she died, filled with decades-old documents. The papers were yellowed and written in neat German.

“She didn’t really talk about it during her life. Not sure why,” Neubeck recalled of her mother. “And I certainly don’t read old German script. So these are intriguing to me.”

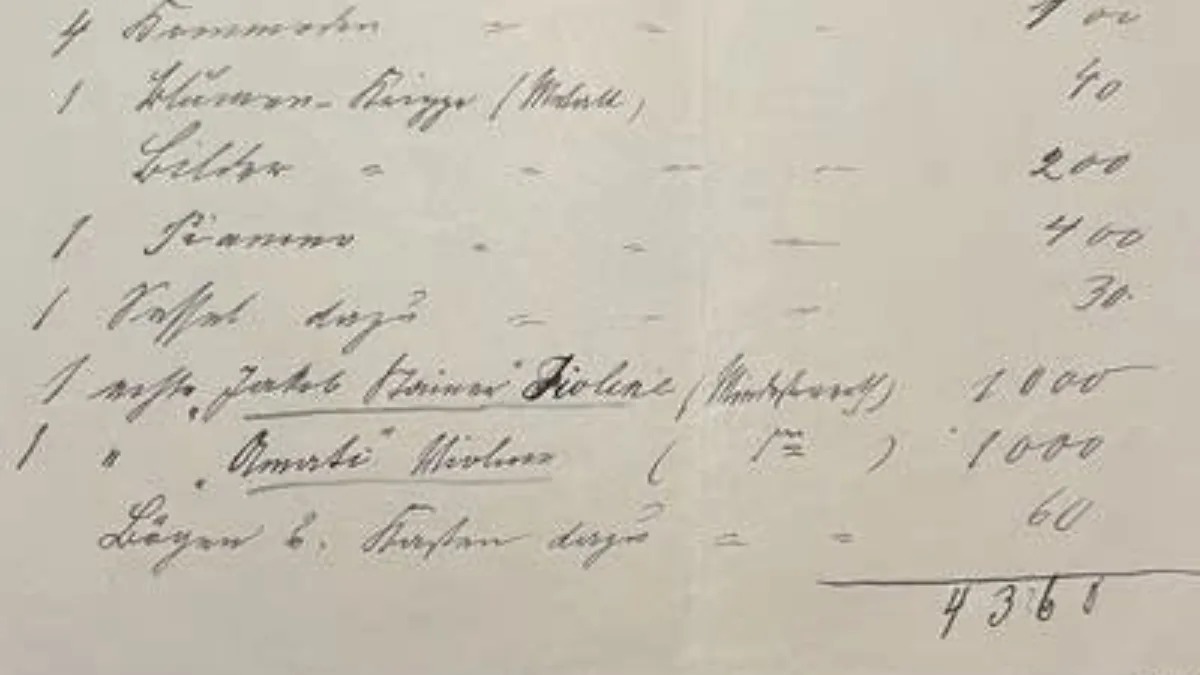

The documents date from 1895 to 2000, including official papers stamped with Nazi swastikas and old newspaper clippings. One document, in particular, caught her eye. One that came from her great-grandfather Hess.

“I call it a dossier of my great-grandfather’s items,” Neubeck gestured to the bottom of the sheet. “And down here the two violins are listed.”

From there, the spark grew into a fire. She knew her great-grandfather owned a music school, which Nazis closed in 1935. Neubeck’s family fled Jewish persecution just before the start of World War II in 1939.

And yet, the violins were nowhere to be found.

“Were those violins stolen by the Nazis, or were they sold because the family was destitute, having lost their music school and their income?” Neubeck wondered.

Continuing to look through her mother’s saved documents she found an appraisal from 1922 from a Berlin luthier, a person who repairs and makes stringed instruments, named Max Möckel, that Hess’ son, Richard, had gone to see.

What are the chances?

From there Neubeck dove further into her research, using all the documents left behind by her mother. She asked for help from friends and art lawyers in California and New York. One of the lawyers, Carla Shapreau, author of the “Lost Music Project” served as a mentor during her search.

Neubeck even contacted the German Lost Art Foundation, located in Madgeburg, Germany, which paid for a researcher to spend six months digging up Neubeck’s family tree. “But there was no evidence of a violin in that,” she said.

Then in 2021, Neubeck received a call from a friend who had been helping with the search. Amy Friedlander, who has a research background, received an online alert.

Neubeck said she picked up the phone and heard, “‘Eva, you won’t believe this, but your document that you sent me from Max Möckel in 1922 just showed up on my computer.’”

A man named Dirk from New South Wales, Australia, had posted a picture of a violin on a site called Flickr, and in the background was a copy of a document Neubeck had in her own mother’s records.

“What are the chances?” Neubeck said.

She learned that Dirk had acquired the violin from his stepfather after he passed away but had no other connection the instrument.

“It was sitting on the floor of his closet,” Neubeck said. “He had no interest in it.”

In 2023, two years after first contacting Dirk, Neubeck negotiated a deal. She would send him $4,000 in the form of a bank check and he would mail the violin. After a hiccup with an incorrect tracking number, she sat and waited.

An heirloom returned

Months later, Neubeck returned home from a film at the Bell Museum in St. Paul about the making of Stradivarius violins. On her door was a note that said a package had been delivered. The post office was about to close so she called.

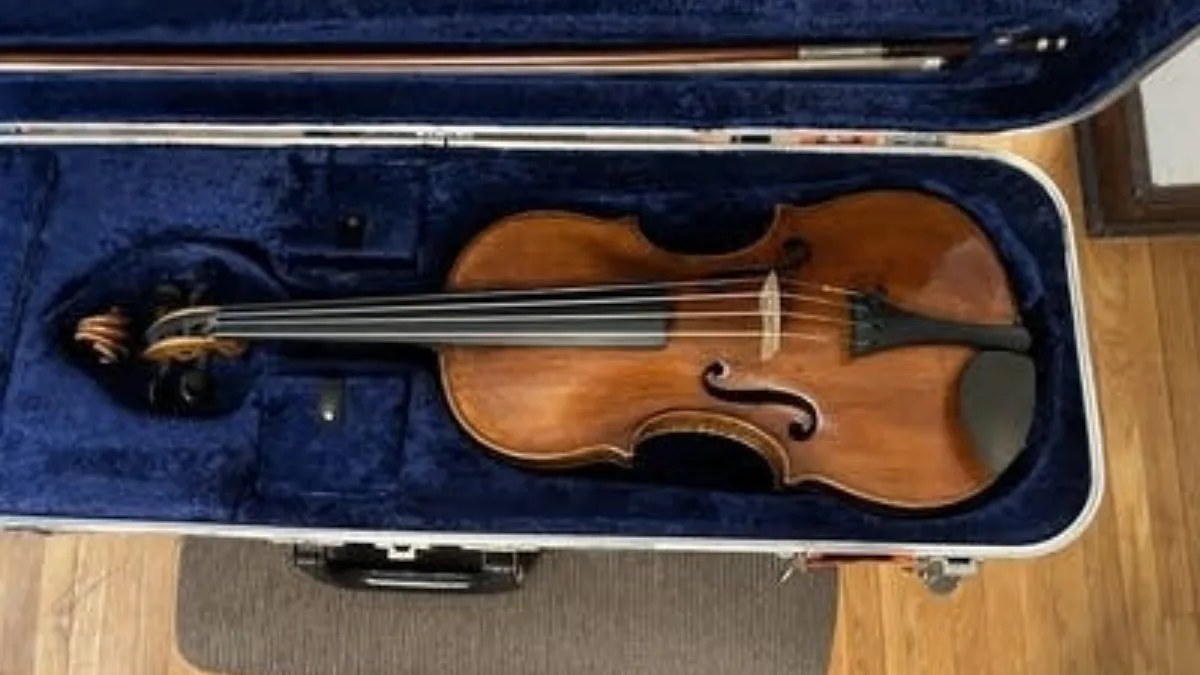

“I said, ‘Please stay open for me,’” Neubeck recalled. She got in her car and drove as fast as she could. What she brought home was a violin case covered in shipping stickers. And inside: her great-grandfather’s violin.

“Look at that grain, it’s lightweight. I can just — it has a presence to it,” Neubeck said. “It’s just like it has energy of itself.”

Neubeck took the violin to Claire Givens, a luthier in Minneapolis, who was able to confirm that it was indeed Neubeck’s great-grandfather’s instrument, and then repair it. “There it is. This survived and is playable,” Neubeck said.

Although Neubeck can’t play it herself, her youngest daughter can and does so every time she visits, bringing life to a piece of history that’s back in the hands of a family who cherishes it.