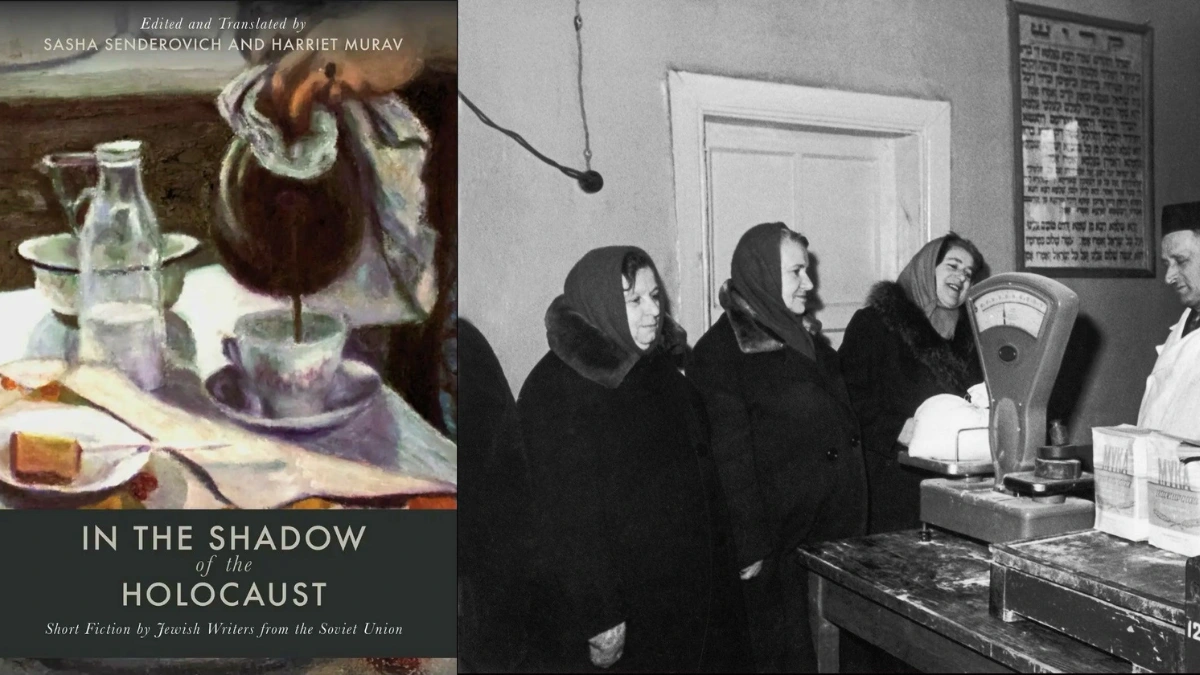

Erno Spiegel’s fountain pen was a subtle weapon in the fight for survival in a Nazi concentration camp.

Holocaust survivor Erno Spiegel, who cared for Jewish twins selected for study by Nazi camp doctor Josef Mengele. (Courtesy of “The Last Twins”)

On May 28, 1944, Hungarian accountant Erno Spiegel, 29, his twin sister, Magda, and their family arrived on a Jewish transport train at the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp in Nazi-occupied Poland.

As they stumbled from a packed cattle car, all their belongings were taken. They were separated by gender. And German soldiers began shouting for “Zwillinge, Zwillinge!” (twins, twins) to step forward.

Spiegel did so, he told his family later, and was brought before the infamous Nazi camp doctor, Josef Mengele, who was studying captive twins. Mengele looked him over and ordered him to take charge of the male twins in his program.

Spiegel said he would need his pen.

The fountain pen, which Spiegel retrieved and then used to falsify records as he helped dozens of children survive the catastrophe of Auschwitz, was donated Tuesday to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington.

The donation came as a new documentary about Spiegel, “The Last Twins,” by filmmakers Perri Peltz and Matthew O’Neill, was scheduled to be screened at the museum on Tuesday evening.

“This is the pen with which I wrote everything,” Spiegel told his son-in-law, according to the film.

The pen, which has been repaired over the years, was donated by Spiegel’s daughter, Judith Richter, 78, of Tel Aviv.

“It’s not just a tool of writing,” Richter said in a video interview last week. It was a weapon that her father used to fight Nazi brutality and to record a dark chapter in human history, she said.

“In the hands of my father in Auschwitz, it became a tool of survival, a means to preserve names instead of numbers, and a quiet act of resistance against the machinery of dehumanization,” she added via email.

Many of the twins in Spiegel’s care came to see him as their guardian. Others called him Uncle Spiegel.

“He was a father figure to us,” said Tom Simon, who with his brother, Peter, were 11 when they arrived at Auschwitz in July 1944, according to the film. “I owe my life to him.”

Gyorgy Kun, who was 12 when he arrived with his brother, Istvan, in May 1944, said: “He knew each and every child as if we were his own.”

The Auschwitz concentration camp complex was one of the sites where the Nazis and their allies killed millions of Jews and others before and during World War II in Europe.

Spiegel and his sister survived. Other members of their family did not.

The twins who were selected for Mengele’s “experiments” at Auschwitz-Birkenau were actually spared immediate death in the gas chambers, according to historians.

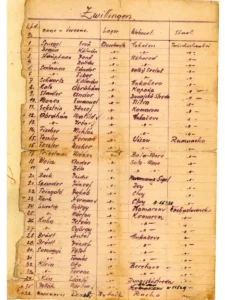

A list of male twins in the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp compiled by Spiegel. (Courtesy of “The Last Twins”)

Most children, along with the elderly and infirm, were put to death upon their arrival, often on orders from Mengele, who selected who would live and who would die. Immaculately dressed, and with polished boots, he would point new arrivals to the left or right, death or life at hard labor.

He became known as the “Angel of Death.”

But Mengele was also obsessed with the study of twins. He sought some genetic insight through the intense measurement of, and cruel experimentation with, their bodies. Often the precise objective was not clear, historian David G. Marwell wrote in his 2020 book “Mengele: Unmasking the ‘Angel of Death.’”

Sometimes, numerous sets of twins were killed with injections, and their bodies autopsied for comparison, according to the 1986 book, “Mengele, the Complete Story,” by Gerald L. Posner and John Ware.

Other twins endured bizarre blood transfusions, surgeries, amputations or purposeful infections.

For all these, Mengele needed subjects.

The result was that Nazi guards — and often Mengele himself — searched the lines of new Auschwitz arrivals for twins, and steered them away from the gas chambers and into a special twins barrack, according to the documentary.

Spiegel, a former soldier in the Hungarian and Czechoslovak armies, said he stood at attention when he was presented to Mengele. Mengele asked him whether he had been a soldier. Spiegel, who spoke Hungarian and German, said yes.

“From now on you are in charge of the twins,” he said Mengele told him, according to Holocaust historian Yoav Heller. “You should know about anything that happens to them.” If anything bad happened, Mengele said Spiegel would be hanged.

Spiegel was allowed to retrieve his pen from a pile of pens that had been left by other Jews, he later told his son-in-law, Kobi Richter, according to the documentary.

He was now in charge of Barrack 14 and a group that later numbered about 50 twins — children and adolescents — and a few who were thought to be twins but were not.