New book ‘Partisan Song’ packs an action-filled punch as it tells the story of Moshe Gildenman, a nearly-forgotten Jewish guerrilla warfare leader against the Nazis in Ukraine

In May 1942, the Nazis murdered 2,200 Jews in the Korzak forest outside Korets, Poland (today in Ukraine). In one day, virtually the entire centuries-old Jewish community of the Volhynian town was wiped out in a mass shooting.

Only 186 Jewish skilled laborers and a few who succeeded in hiding were spared, including Moshe Gildenman and his teenage son, Simcha, and nephew Siomke Geifman. Among the dead were Gildenman’s wife, Golda, and young daughter Feigela.

As the survivors met in one of the remaining synagogues in the Korets ghetto to recite the Kaddish memorial prayer and mark the Shavuot holiday, Gildenman rose and declared, “Know that we’re all going to die, sooner or later. But I will not go like a sheep to the slaughter!… I am not afraid of anyone! I’m not even afraid of death.”1/2Skip Ad

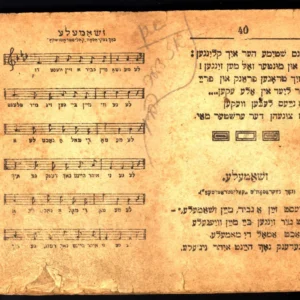

So, when the Nazis entered the ghetto for its final liquidation in late September 1942, Gildenman, his son, nephew, and nine other Jews — armed only with two revolvers and five bullets, and a Yiddish songbook — escaped to join the Ukrainian partisans fighting the Germans and their collaborators before they would be massacred with the others.

The gripping story of how Gildenman, a mild-mannered civil engineer and cultural leader, transformed into a ruthless guerrilla fighter is told in James A. Gryme’s new book, “Partisan Song: A Holocaust Story of Resilience, Resistance, and Revenge.”

To the author’s knowledge, “Partisan Song” is the first work for a general reading audience not only about Gildenman, but also about the World War II partisans who operated against the Nazis in Ukraine.

Musicologist Grymes’s previous book, “Violins of Hope,” about violins played during the Holocaust and the Israeli luthier who restores them, won the National Jewish Book Award for 2014.

He first became aware of Gildenman (also known by his nom de guerre, “Uncle Misha”) when he learned of a musically talented boy named Motele Schlein. The boy, a prodigy violinist, had joined up with Gildenman’s Jewish partisan group after hiding and then fleeing when Nazis deported his family to Auschwitz from the Belarusian village of Karmanovka.

Intrigued by the little-known Gildenman, Grymes continued researching his story, becoming increasingly fascinated by his abilities as a partisan leader and by his musical talents and interests in Korets before the war. Grymes felt he had gained a true grasp of Gildenman when he came across “Freedom Songs,” a book of Yiddish Bundist songs compiled by Joseph Gladstein in the collections of Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center in Jerusalem. As a musician and musical director, Gildenman had used the book in Korets, and he carried it throughout the war.

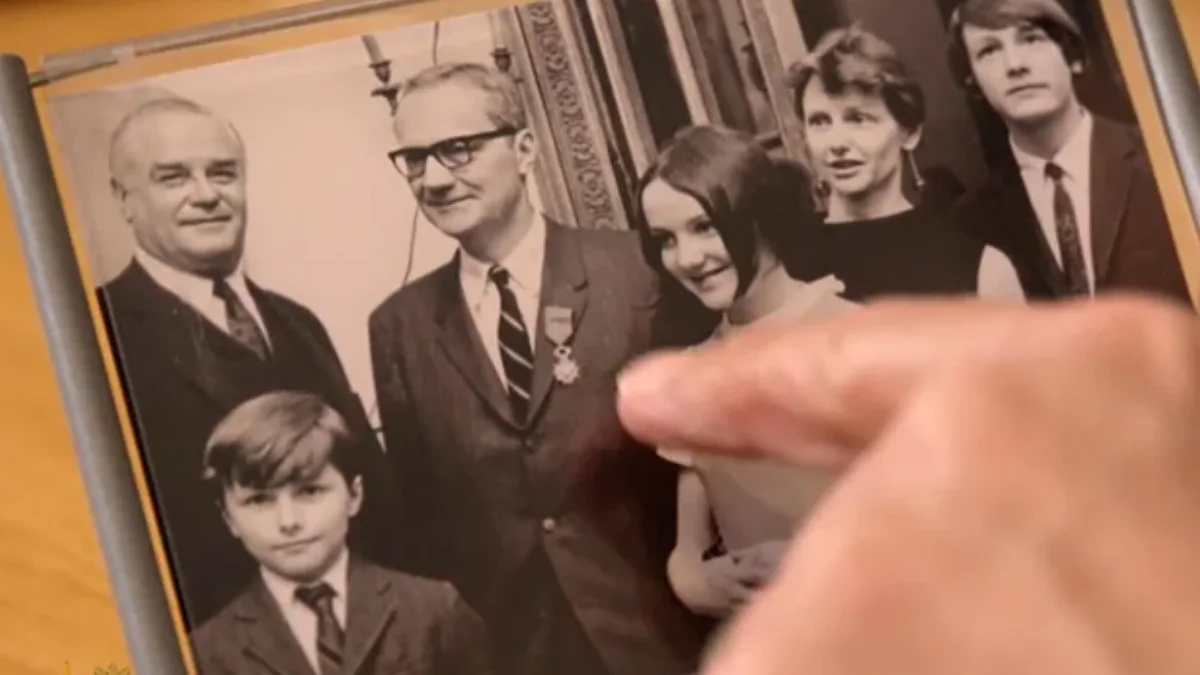

A music ensemble in Korets in the late 1930s. Moshe Gildenman is the second man from the left in the third row. (Family Archive—Polish Roots in Israel Project/POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews)

“That sort of opened up the world of music that Gildenman lived in in Korets. These songs were clearly so important to him that he kept that book with him. He made a little satchel, and there was only a finite number of things he could carry on his person. These were songs he almost certainly knew by heart, because they were fairly well-known. Yet, he decided to hold onto that book,” Grymes.

Each chapter of “Partisan Song” is prefaced with an excerpt from one of the songs in “Freedom Songs,” or from one of the partisan songs that Gildenman’s son Simka collected as mementos from comrades after the war.

While the songs’ lyrics provide insight into the partisans’ outlook and resolve, they merely serve as a framing device. Most readers will instead be drawn in by the non-stop action and drama as the 44-year-old Gildenman became the vindictive killer Uncle Misha. First, his small band from Korets, along with the Jews they met in the forests, organized and fought on their own. A few months later, they joined up with Ukrainian partisans. Known as “Uncle Misha’s Jewish Group,” they fell under Ukrainian command but operated as a separate unit.

Finally, Gildenman’s group was accepted into the Soviet partisans, whose sabotage of infrastructure, destruction of supply lines, and intelligence gathering behind Axis lines were key parts of Stalin’s strategy to keep the Germans tied up, thus making the Red Army’s push westward possible.

Uncredited Valor

In total, Uncle Misha and his group carried out more than 150 combat operations. Toward the end of the war, Gildenman served in the Soviet Army as a combat engineer on highly dangerous missions ahead of the front lines. However, Gildenman and his fellow Jewish fighters did not get the historical credit they deserved.

“There are [Ukrainian partisan] combat logs of what happened… The issue is they never really spoke about the Jewish partisans… [And then] when [Uncle Misha’s group] first joined the Soviet partisans, at least the battles it was involved in are mentioned in the official record, although no credit at all is given to the Jewish partisans,” Grymes said.

Without much — if any — note of the Jewish partisans in the Ukrainian and Soviet records, Grymes faced the challenge of matching Gildenman’s post-war recollections (Spoiler alert: He and his son survived the war) with the official record to create a historically accurate narrative.

“It was interesting to me to see what I could untangle, what I could figure out. Most of the sources were from his writings. Some of the big Holocaust historians [who mention him briefly in scholarly works] were clearly just using his writings without really fleshing them out. So for me, a major moment in the research was when I dug into the partisan records in Kyiv and was finally able to line up his narrative with the historical record,” Grymes said.

He was not surprised that Gildenman, who generally recollected events in association with holidays, actually got dates and places wrong. What he remembered as happening really did happen, just not when and where he thought it did.

“That’s a lot of times the nature of personal testimony. People do not intentionally misremember things, but according to what we know about memory now, things can quickly get convoluted — especially dates and locations. This happens with everybody, but certainly with someone who experienced the trauma of the ghetto, of what happened to his family, and then the years in combat,” Grymes said.

After the war, Gildenman did not return to Korets. Instead, he became a leader in a new community of 27,500 resettled Jewish refugees in Szczecin, Poland. He was active with Ihud (Unity), a Zionist movement that advocated for a shared Jewish-Arab state in Palestine devoid of conflict. He also chronicled and spoke to groups about his wartime experiences as a partisan and soldier, before immigrating to Israel with his son in 1951. He died in 1957.

Grymes can be congratulated for his perseverance in bringing Gildenman’s story to light. However, one is left pondering how the story of such an extraordinary individual was almost forgotten, and reflecting on how historical events can radically change a person.

“That’s the whole arc of his story. He went from being a peaceful community leader to committing brutal acts in the name of revenge. But then the minute the war was over, he just laid down his weapons and lived out the rest of his life trying to re-establish peace,” Grymes said.